Afrikan traditional textiles are a visual representation of history, philosophy, ethics, social conduct, religious beliefs, political thought and aesthetic principles.” – Abraham Ekow Asmah.

The narratives surrounding the origins of the Kente cloth and Kente weaving are of varying measure and degree. Kente weaving is said to be indigenous to the West Afrikan country of Ghana. Some scholars have however forwarded that its origin stems from Western Sudan as far back as the 16th century, and was introduced to the ancestral natives of present-day Ghanaians through trade contacts.

The Ashanti have laid claim to pioneering Kente weaving in Ghana, using an age-old folk story of two brothers (Nana Kuragu and Nana Ameyaw) who learnt the noble art of Kente-weaving by observing a spider spin its web on a farm they visited.

Notable among the arguments concerning Kente’s origins is that of the etymological roots of the word; Kente. Dr Kobla Dotse in his article; The Issue of the Origin and Meaning of Kente (Kete) published on the 12th of July, 2015 argues that the word Kente is a corruption of the Ewe word; Kete. A contrived combination of ‘Ke’ and ‘Te’ both of which imply the spreading of the threads to be woven by the use of the leg pedal and the binding of those same threads using the hands whilst seated in the weaving loom; coordinated actions that result in the production of the ‘Kente’ or ‘Kete’ fabric. Thus, he further argues that the original word for the ‘talking’ fabric is ‘Kete’, as opposed to the more popular ‘Kente’.

Again Dotse et al (2015) make reference to the fact that cotton, which is the base material for the production of Kente (this will be used interchangeably with Kete and they will by reference mean the same thing) was not attainable within the forest belt of the Ashanti Kingdom in the days of antiquity. Cotton was however easily accessible on the plains of the Ewe land and the northernmost parts of present-day Ghana. This singular revelation goes a long way to support their argument that; the origins of Kete and Kete weaving is indigenous to the Ewe land.

We could go forever on the ‘debate of origins’ and albeit important to this piece of knowledge literature, it is however not its primary focus. The weaving of the Kente fabric is not for the mere purposes of clothing and the creation of fashionable attires. It is not a craft invented solely to placate the ego of tribal chiefs and empire Kings. Above every other criterion considered by the inventors of Kete, its role as a medium of storage and communication of ancestral wisdom, knowledge, teachings, customs, practices, rules of usage, conventions and traditions stand undauntedly tall.

The making of the Kente fabric is a sacred process of coding and decoding of secretive age-old cultural and traditional insight.

The large Kete fabric which is what is usually seen as the end product is actually a patchwork of a number of Kete strips. The Kete weaver weaves narrow strips of the fabric and when he has finally acquired the desired number of strips, he proceeds in stitching them together to get the large finished product. The narrow strips, however, have a symbolic meaning; associated with the Mande Dyula tribe that thrived in the days of the ancient Mali Empire. These tribesmen used strips of fabric woven from quality material as a form of currency. They were the gold traders of West Afrika who linked the gold producing forest lands in the South to the North of Afrika.

The strips of woven fabric that are sewn together to obtain the Kente cloth by themselves share with their custodians and onlookers alike this important piece of history. Currency has evolved into the media of exchange we now trade with and the Mande speaking Dyula tribe are dispersed the world over. Kente can, therefore, be referred to as the ‘money fabric’ given the fact that the narrow strips of fabric constituting the final finished Kente product were once upon a time units of exchange wielding great value. The narrow strips, more importantly, talk of the Dyula narrative; of their struggles and cultural moves to seize their fair share of the creator’s given. History is woven into fabric.

Another hidden symbolism of the Kete fabric reveals the message created by the patchwork realized from stitching together the narrow strips of fabric. The overall beauty and underlying symbolic representation of the Kete fabric begin with the narrow strips of woven fabric stitched together to obtain the larger Kete fabric. Given the unique creative intention of each weaver, the strips are designed (in terms of colouring, geometric patterns and cultural symbols) and patched in a way that will bring out the intended message of the fabric.

For instance, each strip that will constitute the finished Kete fabric can be woven into the colours of the rainbow and when they are finally patched, we will have a Kente fabric looking like a rainbow. The colour variation in this instance, however, wields a deeper meaning; red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet are also representatives of ascending levels of human consciousness and a search into their individualized meaning can open one up to the beauty of spiritual enlightenment. Lessons woven in fabric.

Again, cultural symbolism is infused with the making of the Kente fabric. Among the Ewes of present-day Ghana who are credited by some historians as having pioneered Kente weaving, Afiadekemefao is the name given to one of their Kente fabric designs and it roughly means; ‘there is nowhere that is without problems.’ This statement is brief but weighty, for amongst other equally relevant explanations, it points to the difficulties endured by the Ewes during their migration to present-day Ghana; that is to say, they would not have settled here if their original point of settlement was without problems.

So in effect, we are being taught to strive to make the best out of what we are given. Lolozuavi is another creative and philosophical design given the Kente fabric by the Ewes. It roughly means; ‘love has turned into hatred.’ The hands of Capitalism have moulded humans into machines, and machines are incapable of love, only everything else opposite of it. There is a mindless scramble everywhere for the attainment of basic human necessities and men, women and children alike are by the day shedding their humanity so that they can keep up with the pace. It is this observation that has served as one of the bases for the Kente design aforementioned.

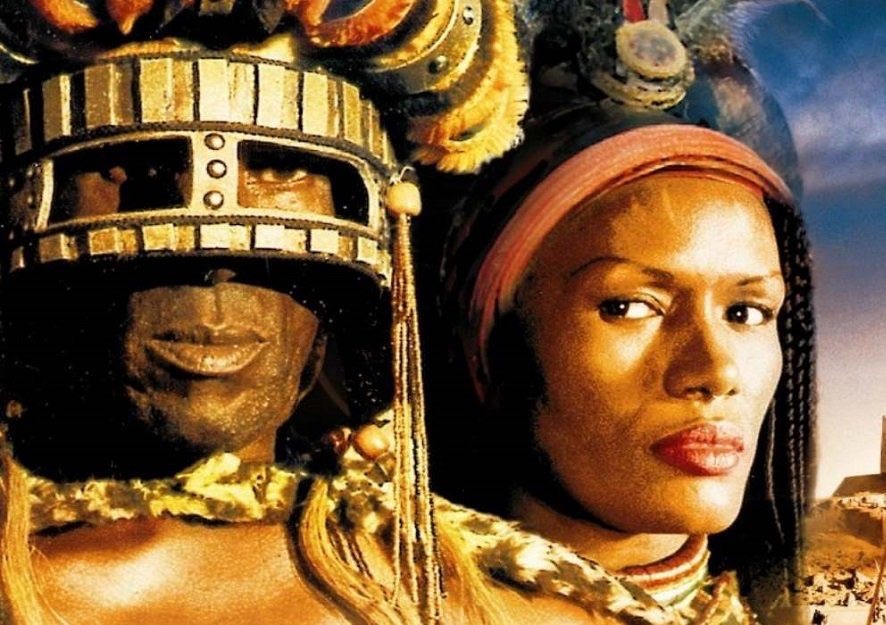

The Akans of Ghana also employ the use of Adinkra symbols; which are pictorial representations of cultural beliefs and traditional truths, in the making of their Kente fabric. They are also known to use geometrical patterns of balanced symmetry as designs in Kente production. The use of geometry takes us back to the holy discipline of ‘Sacred Geometry’ whose basic assumption forwards that; there is a geometrical pattern underlying every observable thing in existence, be it living or non-living. And it is this underlying geometry that is captured and interpreted by our senses to allow for perception. Thus each geometrical design on the Kente fabric speaks of a deeper underlying universal knowledge of our world and the mechanisms that rule it.

The Navajo Blanket of the Native Americans, the Ancient Peruvian Gown of Peru, the Javanese Batik of Ancient Sumerians and the Smock of Northern Ghana are all examples of fabric from cultures who coded and decoded their dear, timeless and forward-thinking narratives, customs and traditions into fabric making so as to preserve their originality and ensure their transmission to present and future generations.